Year A—December 6, 2025

Readings:

Isaiah 11:1-10

Romans 15:4-13

Matthew 3:1-12

Psalm 72:1-7, 18-19

A shoot shall come out from the stump of Jesse,

and a branch shall grow out of his roots.

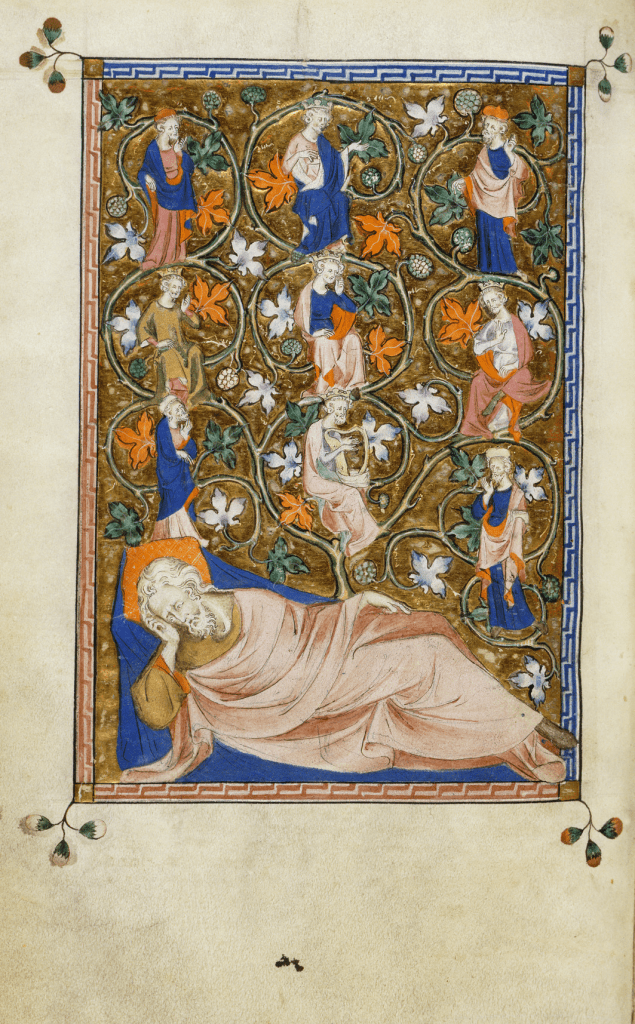

So begins the reading from Isaiah this week. Christians have understood this passage in light of Jesus, who the Gospel writers cast as a literal descendent of David (son of Jesse). The image of the “Jesse Tree” developed, beginning in the 11th century, to show Jesus’ family tree all the way back to Adam and Eve in some cases, but at least back to king David, Jesse’s son. But a few other things are going on in these images.

For starters, why is Jesse shown as sleeping?

One reason is that this posture lends itself to the compositional goals of the artist, to show the tree growing from “out of” Jesse. Also, it may simply be taken from verse 10, which refers to the resting or dwelling place of Jesse’s “root.” But it also alludes to a couple other biblical symbols. First, it brings to mind the story of Adam falling into a deep sleep as God creates a woman from one of his ribs. That the tree growing out of the sleeping Jesse’s side seems to confirm this reading. In addition, it puts us in mind of the common trope of the prophetic dream. While the sleeper here is Jesse but the prophecy is Isaiah’s, nevertheless the outgrowth of Jesse’s descendants leading to Jesus has a dream-like quality. This helps us read the genealogy back into Isaiah’s prophecy, thus reinforcing the Christian reading of the text.

Christian traditions often come into conflict with more recent biblical and historical scholarship, however; and it is good for Christians to recognize that the Hebrew Scriptures have an integrity of their own, without reference to Jesus as the Christ. Biblical scholars (of which I am not one) seem to be split on their interpretations of this whole passage, which apparently shows evidence of redaction—for example, verse 10 seems to conflate the root with the stump or even with the shoot in verse 1:

On that day the root of Jesse shall stand as a signal to the peoples; the nations shall inquire of him, and his dwelling shall be glorious.

However, that verse, which ends today’s lectionary passage, seems to some scholars to be a clumsy attempt to transition from this vision of peace into the rest of the chapter, where God is calling God’s covenant people from out of the nations, leading to political alliances and conflicts alike.

The Septuagint (abbreviated LXX)—an early Greek translation of the Hebrew Scriptures used in the Diaspora by Paul and other New Testament writers—renders verse 10 a little differently. Paul appears to be using the Septuagint when he quotes the passage thus:

The root of Jesse shall come,

the one who rises to rule the Gentiles;

in him the Gentiles shall hope.

In any case, the passage is useful in Paul’s theology. The “Apostle to the Gentiles” seems to have been motivated by passages such as those he quotes in this lectionary passage from Romans—messianic prophecies that extend the worship of Israel’s God to all the nations.

And so Christians, predominately Gentiles within a generation or two after Paul, have fully embedded Jesus Christ into these prophecies as we include them in our own canon of Scripture. Thus, we read today’s Psalm as also talking about Jesus. In its own context, the Psalm is a coronation anthem for a king of Judah. It expresses the hopes of the people for a king: that he might “defend the needy,” “rescue the poor,” and “crush the oppressor;” that he will rule in righteousness; that his lifetime and reign will be long—across multiple generations, “as long as the sun and moon endure,” being pretty obvious hyperbole, but otherwise not too far off from something like, “…Send him victorious, happy and glorious, long to reign over us…” While there is hyperbole, there is also an expectation from the people that their king will seek the common good of the people. Christians read this Psalm, like the vision of the “peaceable kingdom” in today’s Isaiah passage, as primarily eschatological. But maybe we should start expecting righteousness, peace, and good news for the poor to be a more present reality. Maybe we should be demanding that of our leaders. John the Baptist can supply the connection here, I think.

In the Gospel passage for today, John is portrayed as being his usual thorny self. Offering baptism to prepare his fellow Jews for a coming messiah, he nevertheless chided religious leaders—who were answering his call and coming to be baptized—precisely for not bearing fruit congruent with the repentance that baptism signaled. More tree imagery. John continues: Having lineage going back to Abraham doesn’t place you among the righteous; God can cut that tree down and raise up descendents for Abraham from stones instead. Switching metaphors, he declares that the one coming after him, i.e., the messiah whose way he is trying to prepare, is coming, winnowing fork in hand, to separate the wheat from the chaff; he will burn the chaff in “unquenchable fire.” I should think the mere mention of unquenchable fire should sell anyone on being dunked into the Jordan River!

We’re not told if those religious leaders were ultimately baptized by John. Why not imagine the scenerios? What if they were baptized? What would that look like as they went back to their jobs? What if they weren’t? Why might that be? In either case, how would this encounter with John affect any later encounter with Jesus? How has John prepared them?

And where do we go with it? Those of us who, typical Christians, are Gentiles—where do we see ourselves in John’s diatribe? Are we also in danger of being chopped down like a dead tree, or burnt like chaff? Are we the stones raised as children for Abraham? If so, are we being added to the literal children of Abraham? It’s important we Christians don’t write our Jewish siblings out of this story. John is critical of some religious leaders—likely because of their cooperation with the puppet rulers Rome had installed in the Holy Land. For the most part, John was baptizing throngs of people who were sincere in their devotion and repentance—and among whom Jesus was also baptized. Everybody in this story is Jewish.

So today’s readings are a delicate balance for us. They make space for us Gentiles, but as Gentile Christians we stand as successors to a long history of supersessionism, the tendency for Christians to believe we have replaced Jews as God’s people. (As if God breaks covenants—and if God does, then where does that leave us?) Supersessionism is written into our hymnody, our liturgies, and to some extent, our Scriptures; but so is the more biblical idea that we are simply included among God’s people. Or to use another biblical tree image, we’re grafted into Israel.

It’ll ruin Advent for you to a great extent, but I encourage you to pay attention to where our Advent traditions continue anti-Jewish, supersessionist dogmas and sentiments. A season of expectation, anticipation, and preparation, Advent traditionally has a penitential element, and we hear John the Baptist calling us to repentance today. The Incarnate Word comes to us as a Jewish man, from a Jewish mother, and invites us to his glorious dwelling, to join in the worship of the God of Israel as the Gentiles that we are, but now included among God’s people.

Leave a comment