Selection I—All Years

Merry Christmas!

[There are three different sets of readings for Christmas Day. In my experience—admittedly, only with cathedrals—the first set is used on Christmas Eve, while the second and third are used in services on Christmas Day. Since they don’t change from year to year, my intention is to use one each year of the 3-year lectionary cycle.]

A couple years before he released his Christmas CD, Bruce Cockburn included a Christmas song on his 1991 album, Nothing but a Burning Light. That song, “Cry of a Tiny Babe,” includes the lyric,

It isn’t to the palace

that the Christ Child comes

but to shepherds and street people,

hookers and bums.

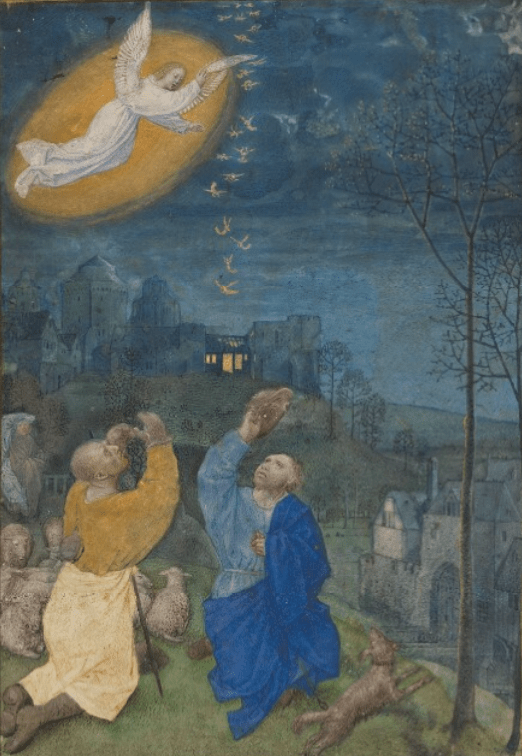

Our lectionary readings include Luke’s scene of the angels apprearing to the shepherds—a story so familiar we can easily tame it. We like the idea of cute, fluffy lambs attending Jesus’ birth. But why did Luke have angels appearing to shepherds at all?

This wasn’t the sort of annunciation Luke earlier described when Gabriel came to Mary with the proposition that she bear the Son of God. This annunciation feels both more distant and yet equally intimate: while hosts of angels in the sky sing God’s praises, an angel speaks directly to the shepherds and tells them to go see Mary’s baby (although the directions are horribly vague).

Could it be that the angels were simply out singing God’s praise, accompanying God the Son into the world, and the shepherds were in the right place and time to catch the vision? If that were the case, wouldn’t the racket have awakened more people in the countryside? Or were the shepherds just particularly receptive to perceiving such things? It could also be that the angel was sent specifically to them, to deliver a message to those specific shepherds, from God. If you’re like me, it’s difficult to decide which of these scenerios is more attractive. I think that as good stories go, this one offers multiple interpretations, and we can think through all those possibilities. What would it mean for God to pick those shepherds out of all the other people around? That Go specifically wanted them to meet God’s Son? That God would want those shepherds in particular to know about this event? Alternately, what would it mean if everyone nearby was asleep and slept through the music of angel choirs, but the shepherds being awake were able to witness it? Or, what would it mean if the heavenly vision were available to anyone who could have perceived it, and it so happened that it was these shepherds who were open to this message? Maybe all three possibilities point to the same conclusion: that, as Cockburn sings, the shepherds are simply the kind of people to whom God Incarnate comes?

Isaiah declares God’s intention to shine light into God’s people’s gloom, to free them from oppression and destroy even the memory of warfare. The birth of a child is invoked as a symbol of hope, the promise of stability under a leader who will fulfill the Davidic ideal of a shepherd-king. Christians have appropriated this passage as an interpretive key to the story of Jesus’ birth. But like Luke’s shepherds, who caught a vision of angels, we can glimpse in this passage God’s will for God’s people: hope, stability, light, and freedom from oppression and fear. “The zeal of the Lord will do this;” this is precisely the sort of thing God really wants to do for us.

The letter to Titus is a curious choice for Christmas, but this passage sort of ties up the other readings with a bow. Luke tells us that the glorious appearance of Christ has happened in history; the author of the epistle tells us to expect it again. In the meantime, what Christ has done for us frees us to live in this world with the same kind of zeal we learn from God through Isaiah.

If the appearance of Christ is about bringing liberty and ending oppression, it’s no wonder the “shepherds and street people, hookers and bums” are uniquely poised to catch angels singing about it. But let’s not romanticize their witness. We are called as a zealous God’s zealous people to manifest “good works”—that is, to do the things God has shown us God desires for our world: to break yokes of bondage and rods of oppression, to destroy the means of warfare that keep people living in darkness. I guarantee that we can learn how to do that in solidarity with our siblings who live out on the streets, who know precisely what Isaiah is talking about.

Leave a comment