The Baptism of Christ

Year A—January 11, 2026

Readings:

Isaiah 42:1-9

Acts 10:34-43

Matthew 3:13-17

Psalm 29

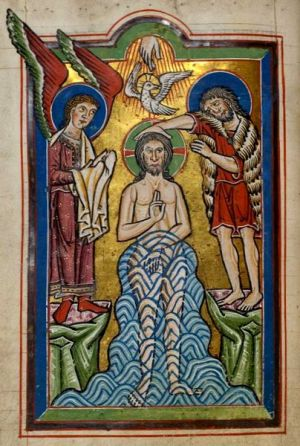

In the West, we call this feast the Baptism of Our Lord, or something similar. In the East, it is the Theophany—manifestation of God—because, for the first time in history, the Holy Trinity is revealed. God the Son is baptized, while God the Father pronounces Jesus to be the Son, and God the Holy Spirit descends in the form of a dove. The iconography here is fascinating and instructive.

First, the depiction of the Jordan River is really odd. Icons, of course, are not intended to depict anything literally; they are visual theology. By showing the waters of the Jordan gathering up Christ’s body even as he holds his hand in a gesture of blessing, we see that in his baptism, Christ blessed all the waters of the earth. I rather like how the Rev. Jeremy McKemy (of the Orthodox Church in America) puts it on his blog:

Jesus is not submerged in the water, for creation was baptized in Him, not vice versa.

—Fr. Jeremy McKemy

Here we see Christ gathering all creation into himself, who was its Creator: we see salvation already proceeding from the Incarnation of God.

Another detail, which we find in Western art as well, is Jesus’ nakedness. When Jesus is portrayed naked (or nearly naked) in art, it is depicting one or both of two things: first, by showing his flesh, it is making the statement that Christ has truly come in the flesh. Second (and this doesn’t only apply to Christ), it represents innocence. Early Christians were baptized naked, though, so this part of the iconography also reflects early Christian practice.

I looked through quite a few images of the Theophany and chose this one, in part, because it clearly depicts both the Father and the Spirit in the ways that are technically permissible in Christian art. We can paint or draw Christ, because he is the image of God made visible; however, the Father and Spirit are not visible to us. Out of caution and respect, the tradition has sided with the prohibition against depicting God (i.e., the prohibition against graven images) except by using symbols. A hand emerging from heaven is the usual symbolic representation of God the Father. The Holy Spirit is usually shown as a dove descending. So here, as the name of the feast suggests, we see the Holy Trinity represented as one, in one scene.

I won’t go into detail about other elements of iconography, except to say that it is normal to feel a little destabilized by them. The gold background alerts us to the fact that this scene, this moment in history, is charged through with glory. That is an excellent link into the Psalm appointed for today in the RCL, particularly the last three verses:

And in the temple of the Lord,

all are crying, “Glory!”The Lord sits enthroned above the flood;

the Lord sits enthroned as King for evermore.The Lord shall give strength to his people;

the Lord shall give his people the blessing of peace.

Psalm 29:9-11

The reading from the Hebrew Scriptures is from Isaiah. Christians have long interpreted it as a prophecy about Christ, but it is clearly about Israel, as we can see in verse 6:

I have given you as a covenant to the people,

a light o the nations…

My own understanding of prophecy in the Bible is that, like prophecy in general, it is less about prediction and more about speaking God’s truth into the world. Prophecy that has been included in the canon of Holy Scripture must be multivalent. It applied primarily to whoever it was addressing in the first place, but generations have found meaning in it as well. We might think of it as an interpretive framework that helps us recognize patterns pointing us to God. For Christians to read this passage as a way of understanding Christ is to light our candle from Israel’s light; neither light is diminished. (That’s good news; it means we can give our light away freely, too!)

The lectionary reading from Acts echoes this sentiment, if we look at it in context. This segment sits among the story of Peter’s vision (the one with the unclean animals he’s commanded to eat) and subsequent visit to Cornelius, a centurion in the Italian regiment. Peter had learned from his vision that he must not call “unclean” what God has made clean; this turns out to be about Gentiles, which becomes obvious to Peter when he meets Cornelius and his friends who, upon hearing Peter’s quick run-down of the Gospel of Christ’s life, death, and resurrection, are filled with the Holy Spirit. Peter’s response is that these Gentiles should also be baptized with water, since God has clearly given them the same Holy Spirit he and the other Jewish Christians were given.

Even before they were baptized with water, these Gentiles received the Holy Spirit through Peter’s ministry of the Word. And why not? Peter’s vision had shown him that God had made all things clean. As the icon above tells us, all things were purified when Christ entered into creation. Without the distinction of clean and unclean, Jewish and Gentile Christians could sit at table together and break bread. Well, that’s an expression; I assume the meat, not the bread, had been the sticking point.

The Gospel passage simply tells us one version of the story of Jesus’ baptism by John in the Jordan. You can see how every detail in that passage comes alive in the icon above. Even John’s protestation, “I need to be baptized by you, and do you come to me?” can be seen in John’s expression. He seems to be hiding his face or redirecting his gaze. Even though he is higher up in this scene, Christ takes center stage and John points us to him. And we see that, as the Word draws the world he made up into himself, this is the work of all three Persons of the Holy Trinity. God the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit create, redeem, and sustain the cosmos in which the Word dwells, and which now dwells in him.

Leave a comment